There are three kinds of children's books I hate the most. One, are the children's books written by celebrities. Two, are children's books that teach an important life lesson with a heavy moral. And three, are children's books in which the illustrator uses some sort of a crafty technique to create the illustrations, aiming for grand effect that lasts exactly a second until the viewers get bored out of their minds because the lack of deliberate details translates directly into a lack of visual information that makes the pictures stupid and uninteresting. Children pick up on this much faster than adults, but even some grown-ups can be taught to look through the pizzaz. One of the worst offenders of this artistic crime is this guy who could be great if he stopped bullshitting (as he did for the The Tale of Despereaux), but his drawings tend to be emotionally and technically ambiguous in a way I really don't like.

This entry, however, is not about him, but about an exceptional book that uses a crafty technique and teaches a valuable lesson, and nevertheless happens to be one of my favorite picture books of all times.

Wave is a book that explores the ancient theme of "man vs. nature", where the "man" happens to be a little girl, and "nature" happens to be the ocean, on one of whose beaches the little girl finds herself, for what looks like the first time.

The story is told in pictures only, no words. However, since the author/illustrator Suzy Lee can actually draw, a skill so many contemporary illustrators profoundly lack, the narrative is exceptionally clear, nuanced, and complex. The pages are split so that the little girl and her seagull entourage are on the left page, and the ocean is on the right up until both parties brave the unknown and venture onto each other's territories with wonderfully joyous and exciting results.

The illustrations are a done in pencil for the girl and the seagulls, and a blue watercolor(?) resist wash which makes the wave and the ocean simply beautiful and very accessible for children. The way the interplay is set up between the two pages is comparable to the use of image size and page spillover in the Wild Things, which is probably the highest compliment of a comparison one could make towards a picture book.

One of my other favorite things about Wave, is that there is a real sense of danger in the story. The mom, who we see on the title page bringing her little girl to the beach, sits under her umbrella in a space off the edge of the page, so that we only see the girl alone. The ocean is much larger than the girl, and the wave reaches well above her head when it comes, and on one of the page when the wave comes over onto the girl's half of the book, it covers the girl entirely. I like this honesty and sense of risk that you feel when reading the story. I am glad everyone is ok, and as the wave retracts back into the ocean it leaves sea treasures for the little girl to play with, but I also like that something scary must be overcome before comfort and understanding can be achieved. I love the fact that many of the implications of this story can never really be articulated in words.

I have been wholeheartedly recommending this book to my friends for many years now (as well as the other Suzy Lee books about which I will most certainly write very soon), but having my own little girl who has been playing on the beach and encountering the waves has made me appreciate this book on a whole new level.

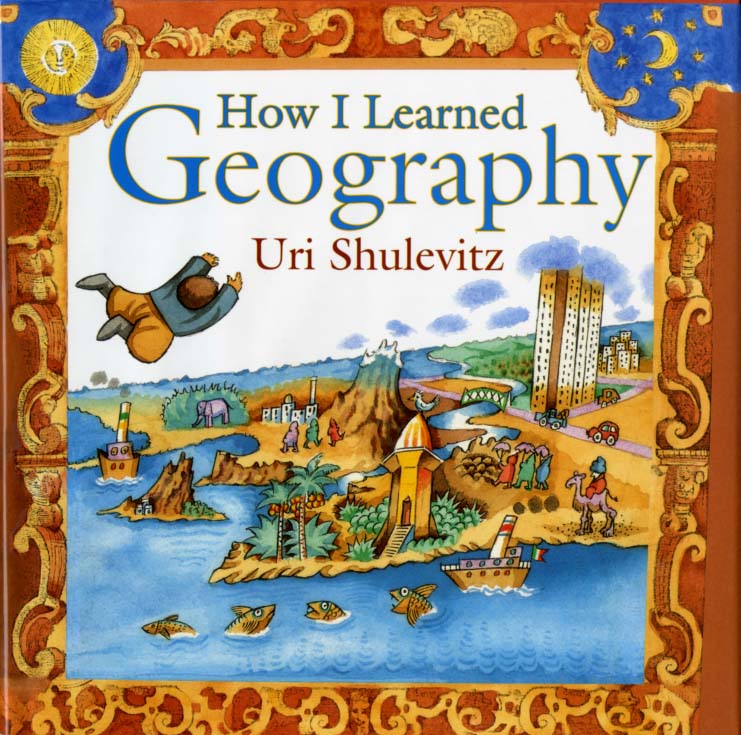

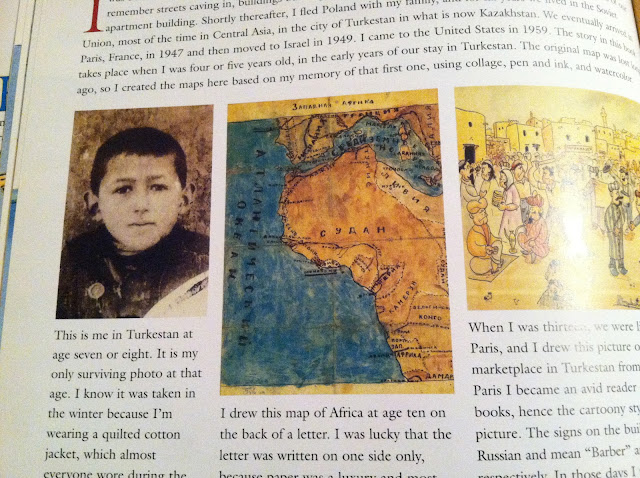

Uri Shulevitz is a hard person for me to write about because he has written and/or illustrated a very large number of books about which I have drastically different opinions, but I'll just focus on this one. I think this is by far the best book Shulevitz has written.

Uri Shulevitz is a hard person for me to write about because he has written and/or illustrated a very large number of books about which I have drastically different opinions, but I'll just focus on this one. I think this is by far the best book Shulevitz has written.

I checked this book out so many times from the library at the school where I worked once that the librarian just gave it to me. It was quite a generous gift (though I did donate a bunch of books in exchange) because this book is out of print and while you can still get a used copy it is quite expensive.

I checked this book out so many times from the library at the school where I worked once that the librarian just gave it to me. It was quite a generous gift (though I did donate a bunch of books in exchange) because this book is out of print and while you can still get a used copy it is quite expensive.